- Home

- Marilynne Robinson

Lila Page 5

Lila Read online

Page 5

But Lila could read, and Doll was glad of it, no matter what anybody thought. She said it would come in useful. Maybe it would sometime. Mostly Mellie was right—it told her what she’d have known anyway. NO HELP WANTED HERE. It had been good for knowing the names of towns that were too broke and forgotten to need names, which is why you had to read the sign to find it out. Still, when she was getting a can of beans and a spool of twine at the store, she had bought herself a tablet and a pencil. She was just curious to know what she hadn’t forgotten yet. She had turned down the corner of that page, and she copied out those words. And as for thy nativity, in the day thou wast born thy navel was not cut, neither wast thou washed in water to cleanse thee; thou wast not salted at all, nor swaddled at all. No eye pitied thee, to do any of these things unto thee, to have compassion upon thee; but thou wast cast out in the open field, for that thy person was abhorred, in the day that thou wast born. And when I passed by thee, and saw thee weltering in thy blood, I said unto thee, Though thou art in thy blood, live; yea, I said unto thee, Though thou art in thy blood, live. She thought, First time I ever heard of salting a baby. She made the letters slowly and carefully, not so easily even as she had made them as a child, but she told herself she would write a little every day. Practice, the teacher said, when her lessons were so clumsy-looking beside all the others that she was shamed almost to tears. You just need a little more practice.

And she began to look forward to morning. As soon as there was light enough, she sat at the door with the tablet on her knee and wrote. She copied words, because she wasn’t sure how to spell them, and this was a way to learn. Who would ever know if she spelled them wrong? Nobody ever came around. Still it shamed her to think how ignorant it might look to her if she weren’t too ignorant to know any better. So she wrote, In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was waste and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. Waste and void. Darkness was upon the face of the deep. She would like to ask him about that. She wrote it all again, ten times.

She enjoyed a morning when the heat was coming on and she was still a little cold from washing in the river. At dawn the chant of the crickets and grasshoppers and the tree toads and cicadas was already slow. It was as if the heat and sunlight were taking more than they were meant to take, more damp, more smell, just because they could. They were so strong, and nothing else was really awake yet. There was a feeling of something like injury about the earth smell and the dew smell, the leaf smell. The tansy didn’t bother her so much anymore. Doane said deer hate tansy, and maybe that was why they hadn’t found the squash growing by the cabin, just a few seeds left lying by the stump other people had used to chop wood and clean fish and gut rabbits. She planted them, and now there were big, tented blooms, yellow as could be, and big vines trailing over the ground. She hoped the old man did not know where she was staying, and she knew he would never come there if he did. But if he ever did come, she hoped it would be in the morning. Those little white moths fluttering over it made that raggedy old meadow seem almost like a garden.

When they were children they used to be glad when they stayed in a workers’ camp, shabby as they all were, little rows of cabins with battered tables and chairs and moldy cots inside, and maybe some dishes and spoons. They were dank and they smelled of mice, and Marcelle made everybody sleep outside except when it rained, but they always had a cabin, and they kept everything they carried in it during the daytime. And Lila and Mellie and the boys, when they weren’t working, played that it was their house or their fort or their cave. They would search it for anything that might have been left there, and if they found half a bootlace or a piece of a broken cup they would make up stories about what it was and why they were lucky to find it. Once, Arthur’s boy Deke found a penny that had been left on a railroad track and squashed flat. He held it up to the door and put a nail through it. Somebody sometime had nailed a horseshoe above the door of a cabin they had for a week, and they felt this must be important. They were wary of the strangers and hostile to their children, except for Mellie, who always wanted to play with the babies and would be just sociable enough to get their mothers or sisters to let her. Mellie playing mumblety-peg and tending a grubby infant between turns, hum-hum-hum, rocking it in her bony arms, playing at mother and child.

They would all be working in the orchards, picking apples or cherries or pears. They would be up in the tops of the trees all day long, and they would never spill a basket or break a branch. It was work children did best. They were given crates of fruit that was too ripe or bruised, and the children ate it till they were sick of it and sick of the souring smell of it and the shiny little black bugs that began to cover it, and then they would start throwing it at each other and get themselves covered with rotten pear and apricot. Flies everywhere. They’d be in trouble for getting their clothes dirtier than they were before. Doane hated those camps. He’d say, “Folks sposed to live like that?” But the children thought they were fine.

She would tell the old man, I didn’t use to mind tansy. I still like an apricot now and then. She pretended he knew some of her thoughts, only some of them, the ones she would like to show him. Mellie with her babies. Doll smiling because she had a bit of sugar candy from the store to slip into Lila’s hand when the others weren’t looking. Any one of them could walk through that field, plucking at the blue stem and the clover, thinking their own thoughts, natural as could be. They had passed through so many other places just like it, a whole world of weedy, sunny, raggedy fields with no names to them. Only that one name, the United States of America. If they could be there the way they were in her mind, before the times got hard, then he could know them. She would want him to know them.

No. Why did she let herself think that way? If he saw this place he would just be embarrassed at how poor she was, how rough she lived. He wouldn’t quite look at her, he’d try not to look at anything else, and he wouldn’t say much at all. She’d be hating him and hoping he knew it. Then when he was gone she would have all that kindness to deal with. And she hadn’t even saved up enough yet for a bus ticket. Maybe that is the one thing she could bring herself to ask them for. A ticket out of town. She’d probably have one in her hand before she finished asking.

So she started copying again. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. She wrote it out ten times. If she could make herself write smaller, she wouldn’t fill up the tablet for a while. She wrote Lila Dahl, Lila Dahl, Lila Dahl. The teacher had misunderstood somehow and made up that name for her. “You’re Norwegian! I should have known by the freckles,” she said, and wrote the name down on the roll. “My grandmother is Norwegian, too,” and she smiled. At supper, when Lila told her what had happened, Doll just said, “Don’t matter.” That was the first time she ever thought about names. Turns out she was missing one all that time and hadn’t even noticed. She said, “Then what’s your last name going to be? ’Cause it can’t be Dahl, can it?” and Doll said, “That don’t matter, either.”

She couldn’t keep the Bible and the tablet in her suitcase, because that was the first thing anybody would steal. Her bedroll would be the second thing. She had put the money she was saving in a canning jar under a loose floorboard, but it was too dirty down there for anything else. It was really just the clumsiness of the writing she wanted to hide, because she thought, What if he saw it? Then she thought, That’s what comes of spending all this time by myself. So she set them on top of the suitcase, thinking a thief would probably just clear them off there and leave them lying on the floor, since they weren’t worth anything. And anybody who would steal from her was probably twice as ignorant as she was and wouldn’t take any notice of them anyway.

The thought came to her that very morning. Why was she always walking into Gilead? There were farms

around. One of them must need help. Anyone who saw her could tell she was used to the work. Those folks in Gilead knew her too well. She was tired of it. And when she asked herself that question and answered it—No good reason—she felt as though she had put a burden down. It used to be when they were with Doane and Marcelle and they had to pass through a town, they’d clean up the best they could first, and then they would walk along together, looking straight ahead, as if there could not be one thing in the whole place that would interest them. Town people thought they were better. They all knew that, and hated them for it. Doane or Marcelle might go into a store to buy a few things they needed and a little bag of candy or a jar of molasses, but the rest of them just kept walking till they were out in the country again. Somehow Mellie would have figured out hopscotch, never seeming to watch the girls that were playing at it in the street, and that would be all she and Lila thought about for days afterward. They left a trail of hopscotch behind them, Mellie always thinking of ways to make it harder. They’d be jumping along in the dust, barefoot, with licorice drops in their mouths, feeling as though they had run off with everything in that town that was worth having.

Walking into Gilead, she felt just the way she had felt in those days, except now she was alone. Doane used to say, We ain’t tramps, we ain’t Gypsies, we ain’t wild Indians, when he wanted the children to behave. She asked Doll one time, What are we, then? and Doll had said, We’re just folks. But Lila could tell that wasn’t true, that there was more to it anyway. Why this shame? No one had ever really explained it to her, and she could never explain it to herself. Thou wast cast out in the open field. All right. That was none of her doing. She had worked herself tough and ugly for nothing more than to stay alive, and she wasn’t so sure she saw the point of that. Why did she care what people thought. She was nothing to them, they were nothing to her. There really was not a soul on earth she should be worrying about at all. Especially not that preacher. Doll would be glad to see her no matter what. Ugly old Doll. Who had said to her, Live. Not once, but every time she washed and mended for her, mothered her as if she were a child someone could want. Lila remembered more than she ever let on.

Those thoughts. Still, she would go down the road until she saw a farmstead, and then she’d just look for someone to talk to and ask. Simple as that. And she’d take some sort of hard work that would wear her out, and then she’d sleep. No dreams and no thinking. No Gilead.

And things did turn out well enough. At the first house she went to there was an old farmer with a sickly wife and a son in the army. There was nothing they didn’t need help with. They told her right away that they didn’t have much money, and she told them she didn’t expect much, so that was all right. It took her most of the day to clean up the kitchen. She would have liked to work outside, but the woman said she’d always taken pride, and now with her health gone bad on her—so Lila scrubbed it clean, every inch of it. And she did some of the wash, in the yard, at a silver metal tub on two sawhorses. She had a big brown block of homemade soap and a washboard, and she had to heat water on the kitchen stove and carry it outside. It did wear her out. She could hardly lift her arms to pin the clothes to the clothesline. The wash would have to stay on the line overnight, but there was no sign of rain and so much wash to do that she had to make a start on it.

She was back the next morning. The farmer had brought in eggs for their breakfast, and there was ham. They told her she had answered their prayers, and what was she supposed to say to that? After a few days they gave her a ten-dollar bill and a plucked chicken and a decent pair of shoes. And they said they were pretty well out of money until they got a check from their son, who was sometimes a little late with it but almost never forgot. And they gave her a carpetbag with some old clothes in it. So that’s the end of that, she thought. Well, it ain’t the only farm.

There was a red blouse in that carpetbag. It looked almost new. It had long sleeves and a collar and a ruffle down the front. Never in her life before had she worn anything bright red. As soon as she took it out, as soon as she had tried the length of a sleeve against her arm, she decided she might as well take a day off tomorrow and go over to town, maybe with ten dollars in her pocket, just for the feeling of having a little money. Tired as she was, she didn’t sleep. She bathed in the river in the morning dark, then she sat in the doorway waiting for enough light to let her do her copying. And there was evening and there was morning, one day. She didn’t feel like spending much time on it. But she did write it out again and again, as she always did. Lila Dahl, Lila Dahl. Practice. And then she fell asleep. She had been sitting there in the morning sunlight when a sweet weariness came over her, and she had to lie down just for a little while. When she woke up the sun was high, the day half gone. But it is hard to regret sleep like that, even though it was looking forward to the day that had kept her awake all night. She combed out her hair and put on Mrs. Graham’s skirt and the red blouse.

At the store she bought some threepenny nails so she’d have a way to hang things up if she wanted to. The one nail someone else had put in a wall had that chicken hanging from it by the twine around its drumsticks. She’d roast it when she got home. She bought a box of matches. A can of milk. Then she thought she might walk past the church. There was a hearse idling there, and just as she was about to go by, the church doors opened and a coffin came out, four men carrying it, easing it down the stairs. Then the preacher came out after it, his black robe fluttering in the breeze, his Bible in his hands, his big, heavy old head bowed down. She knew it must be some friend of his who was dead. He had so many, one of them was always dying. The men slid the coffin into the hearse, but the preacher glanced up and saw her there and stopped where he was, on the step. The mourners stopped behind him, weeping, and not quite sure what to do, since they seemed to think they shouldn’t step around him. So they wept and hugged each other, and he just stood there, looking at her. The look was startled. It meant, So you’re here, after all! How could you let me think you had left! As if there was something between them that gave him the right to be hurt, the right to be relieved. And she hadn’t even missed church lately. So he was aware of her all the other days, knew somehow that she was close by, or that she was not, and it grieved him that she had been gone from Gilead even a little while. The widow or the mother or whoever she was said a word to him, and he nodded and went on. She saw him standing near the hearse, holding the mourners’ hands, touching their arms, murmuring to them. What do you say to them, she thought, when they stand around you like that, like they just need to hear it, whatever it is? I want to know what you say. She couldn’t walk up to them, stand there with them hearing the words he whispered, waiting for him to touch her hand. She didn’t even have much to cry about. That woman put her head on his shoulder, sobbing, and he put his arm around her and held her there. He pushed her hair away from her face. Lila blushed to think how good it must have felt to her, to rest her head that way.

Well, Lila thought, can’t stand here staring. He ain’t going to look my way again. The hearse had to follow the road up to the cemetery, but the old man and most of the mourners took the path. She wanted to wait for him somewhere so she could speak a word to him, but what would she say? I’m back, I ain’t going nowhere? That probably wasn’t even true. She couldn’t just stay around because she thought it might matter to him. Then the cold weather would come and he’d be thinking about something else entirely. Somebody else to feel sorry for. Her stuck in Gilead with no reason to be there and no place to stay, knowing he would never look at her that way again, if he ever really did even once. Staying on anyway because the thought of him was about the best thing she had. Well, she couldn’t let that happen. Doll said, Men just don’t feel like they sposed to stay by you. They ain’t never your friends. Seems like you could trust ’em, they act like you could trust ’em, but you can’t. Don’t matter what they say. I seen it in my life a hundred times. She said, You got to look after your own self. When it comes down to it, you�

��re going to be doing that anyway.

Lila had money in her pocket. She went back to the store and bought a pack of Camels. On the way home she stopped and lighted one, cupping her hand around the flame, that old gesture. But it had been a long time, and whatever it is about cigarettes went straight to her head. Like I was a child! she thought. Oh! Well, I just got to do this more often. Here I am walking along the road all alone smoking a cig. They got hard names for women who do that kind of thing. I got to do it more often.

She had a habit of gathering up sticks, firewood, wherever she saw it, and she had a lot of it, so she could make a fire that would be hot enough when it burned down to roast that chicken. It was good of those people to pluck it and gut it before they gave it to her. She could put a stick through it and prop it up somehow, and spend the evening tending it, and eat it in the dark, in the doorway. She might go over to that farm the next morning and do some chores for them, because they gave her too much for the work she’d done. It didn’t set right. That would be Sunday morning.

It wasn’t the only time she’d felt like this, it surely wasn’t. Once, Doll went off by herself for a few days, after things started getting bad. When they were looking anywhere for work they must have wandered into a place Doll knew from before, and she had gone off on some business of her own and left Lila behind with the others. She’d never done that, not once. Lila had never spent an hour out of sight of her, except the time she spent at school, and then she hated to leave her and couldn’t wait to get back to her, just to touch her. Doll was always busy with one hand and hugging her against her apron with the other. That time she left Doane’s camp she didn’t tell any of them where she was going, but she did say she would be back as quick as she could. Lila had never really noticed before that the others didn’t talk to her much. She was always with Doll. Once, Marcelle called them the cow and her calf, and Doane smiled. That was after Tammany, when feelings were sore and even Mellie wouldn’t have much to do with her. Lila just kept very quiet and helped with whatever she could. By the second day she already felt them hardening against her, and by the third nobody looked at her, but they looked at each other. There was something they all understood and she should understand, too. On the fourth day, early in the morning, Doane said to her, Come along, and Arthur was with him and Mellie, and they walked down the road into some no-name town, right straight to the church. Doane said, Lila, now you sit on them steps and somebody will come along in a while. You stay there. Mellie don’t need to stay. You mind and you’ll be all right. Hear me, Lila?

Housekeeping: A Novel

Housekeeping: A Novel Lila

Lila Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution

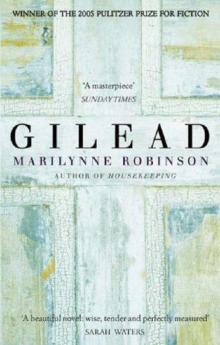

Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution Gilead

Gilead What Are We Doing Here?

What Are We Doing Here? Home

Home Jack

Jack Mother Country

Mother Country Lila: A Novel

Lila: A Novel Gilead (2005 Pulitzer Prize)

Gilead (2005 Pulitzer Prize)