- Home

- Marilynne Robinson

Mother Country Page 7

Mother Country Read online

Page 7

In a book entitled Observations on the Sources and Effects of Unequal Wealth (1826) the American socialist L. Byllesby noted dryly that Owen paid only the standard factory wage and realized a healthy profit. He objected that it was still required of “the producers to surrender a part of the avails of their labor to those who hold a claim of proprietorship over the necessary means for putting their labours to use.” Aside from its interest in establishing a sense of the terms of political discourse in America and before Marx, this criticism is a fascinating early example of the American tendency to miss the point entirely where British social reform is concerned. Owen was making a demonstration of the fact that, properly supervised, rationalized, and instructed, working-class lives could be lived decently and wholesomely at market wages. His experiment tended to prove the old wisdom that the “labor fund”—the sum of money considered to be available in the economy to be paid out in wages without inhibiting the creation of capital, thereby diminishing total wealth—was sufficient to provide adequately for workers. Truly what Owen attempted was the minimum of change, in effect a vindication rather than a reform of the capitalist system—and by capitalist I mean exactly what Marx meant, a system in which a working class is exploited to produce wealth in which they have no share, a system which considers subsistence an appropriate compensation for the mass of people, and an appropriate condition of life.

A partner in New Lanark was Jeremy Bentham, who devoted much time and thought to designing a perfect pauper asylum. It was, of course, a workhouse—which still meant “factory.” Bentham’s scheme would find labor suitable to the varying powers of its inmates, so that the very old or young or ill could make themselves useful. He proposed that children born to inmates be detained into their early twenties—that is, through their peak earning years. Altogether, he felt confident that he could turn pauperism into profit. He dreamed of a chain of these asylums, built on a plan that would facilitate supervision of work and policing of morals, as well as the combining of duplicated work, such as the cooking of meals. He reasoned that such good order would create positive happiness, especially among those who, lacking experience of the outside world, could not make comparisons. This vision of philanthropy does not seem to me remote from the system Bentham realized in partnership with Owen. Both dream of creating a circumstance in which profit and happiness will be maximized together, a sort of transfiguration in which the factory system will be revealed in glory. Certainly the condition of Bentham’s paupers approached nearly enough to the conditions of his and Owen’s employees to demonstrate how very fine a distinction it was that separated the great class of the poor into two great categories, worker and pauper, whether as objects of philanthropy or of punishment. In fact, to distinguish between them is usually an error. A History of Socialism by Thomas Kirkup (1906) reports that five hundred of the two thousand workers at New Lanark when Owen came there in 1800 were children “brought, most of them, at the age of five or six from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh and Glasgow.” In other words, the exploitation of the work of child paupers of which Bentham dreamed was already carried out on a very significant scale. It is startling how often British philanthropists have dreams which if they were to wake they would find true.

The American Byllesby criticized New Lanark on the grounds that it was a profit-making scheme and that it was “directed primarily, to the better formation of human character, and secondarily to ameliorating the condition of the labouring or productive classes.” Byllesby feels this is putting the cart before the horse, that “if pecuniary concerns are first put in a train of amendment, or reform, the human character will, of itself, keep an equal pace in the expansion of its amiable traits, and suppression of its evil capabilities.” But, again, Byllesby has missed the point. His assumptions are the individualist kind, for which we have long been notorious. Owen has no place in his system for “the human character”; it is the worker he is concerned with, a being wholly defined by his class status and his economic function. Owen’s object is to fit him humanely to a role he must occupy in any case.

Owen’s experiment is said to have inspired no imitators in Britain. This remark is misleading, since it implies that the project was a true innovation and that subsequent practice bore no relation to it. Owen set about to stabilize workers in their condition as workers, that is, to proof them against the vices and accidents that created illness, misery, and degeneracy, by regulating the particulars of their existence. It was simply a repetition on a smaller scale and in a more sanguine spirit of the great British project of balancing the working class on the knife edge of subsistence. The minimum of national wealth allowable to the working class was the amount that maintained them in health and vigor. Failing this standard, they fell into illness, despair, and indigency, and became unproductive and, compounding every evil, a charge on the taxpayer. The preempting (exactly the right word in this context) of such small choices of food, drink, and use of leisure as were available to workers encroached far on the small freedom of unenfranchised people. But Owen did not object to actual slavery. Byllesby’s assumption that human nature would flower spontaneously if economic injustice were ended is not a variant of Owen’s idea but its opposite.

From 1838 to 1848 the Chartist Movement, a huge and truly popular call for specific political reforms—universal manhood suffrage, annual parliamentary elections, secret ballot, equal electoral districts, removal of property qualification for members of the House of Commons, and pay for its members—made its long transit across the skies and vanished. It was important because it expressed the views of the mass of people about where their salvation lay. Thomas Carlyle, often listed with Robert Owen among the great social critics of the era, heard Chartism as an inarticulate groan, its true meaning being, “Guide me, govern me! I am mad and miserable and cannot guide myself!” In his view it signified the need of the great mass of people to be truly governed by their natural superiors. He argued that the “free Working-man” should “be raised to a level, we may say, with the Working Slave … Food, shelter, due guidance, in return for his labour.” In typically febrile language, Carlyle expressed the view that carried the day—minus, of course, slavery, which shocks the modern reader, but which had plausible humanitarian arguments to be made for it over and against the situation of the British working class, who were utterly destitute when they were of no economic use to anyone, and who were without resource from the day they became too ill or frail to market themselves as labor. That a change in the legal status of powerless people should be expected to so revolutionize established norms of conduct toward them simply expresses Carlyle’s positive feelings about slavery, which he elsewhere likens to matrimony.

But just to the extent it might be assumed that slavery involved some obligation to sustain the worker in sickness as well as in health, in infancy and in old age, slavery would be a bad bargain. To the extent that the purchaser of labor has an economic interest in the well-being of the laborer, he is restricted and encumbered in the matter of working conditions, for example. And to the extent that he can purchase labor as a commodity, abstracted from whatever vulnerable creature yields it, of the best available quality and in the quantity that suits his needs from day to day, he has a vastly cheaper labor source than slavery. Therefore, Carlyle must make his case for slavery on humanitarian grounds.

Modern American commentators take Carlyle to be decrying the crimes of capitalism, which means our crimes, and the inhumanities of our interrelations. Sensing rebuke, they fall to tugging their forelocks and, thus occupied, are too busy and too happy to wonder about the sort of social criticism that would idealize slavery (though, in fairness, it should not be assumed that these commentators have in fact read Carlyle, rather than merely having acquired a phrase from him in the course of their education).

Carlyle, like the less objectionable Owen, is an example of the most characteristic feature of British thought; that is, the tendency to criticize in such a way as to reinforce the system

which is supposedly being criticized. The essay Chartism is, first of all, a defense of the New Poor Law, whose draconian provisions Carlyle laments roundly—before putting his blessing on them. He is telling his wealthy audience that they should utterly disregard the political demands of the lower orders, that these demands have a significance just the opposite of their intended meaning, that they are a cry not for greater freedom but for less, and that they in fact justify a vastly greater intrusion into the lives of poor people than the New Poor Law itself accomplished. Quite hilariously, he denounces laissez-faire as a doctrine which permits the working class to do as it will, and freedom, he says, has been its ruination. In the face of the undeniable misery which has been the consequence of the stewardship of the governing classes, and in the face of popular demand for an expansion and reconstruction of representative government, Carlyle argues—to the sort of audience sure to be receptive—that England is unhappy because the naturally superior have not governed with sufficient thoroughness.

This is more than flattery—although it is most certainly flattery, too. It is a call to reform, of a kind taken very seriously, not least because it represented so small a departure from established practice. Regulating the poor had been the great preoccupation of British social thought from its precocious beginnings, always with the same object, securing ample labor at a favorable price. In defense of the severity of the New Poor Law, Carlyle argues that everyone should work or die—and that the poor should take it as an honor that their lives will be the first to feel the force of this great principle. Slavery is one logical extension of the sort of thoroughgoing, personal governance, uncomplicated by redundancy, of which, in Carlyle’s view, the mass of men stood desperately in need.

British social thought may as well be imagined as occurring this way. It takes place in a country house built and furnished to accord with conventions polished by use, a house filled with guests, great and minor luminaries, ornaments of literature, the sciences, the church, and of philosophy and politics. Most of them, not coincidentally, are cousins at some remove. They are charmed to find in one another just that streak of intuitive brilliance they had always admired in themselves, and to be confirmed in their sense that they are true members of a group in which there are no impostors, by a very great similarity of taste, of interest, of sympathy. It is a leisurely visit, some centuries in length, and in due course everyone has confessed his weakness for Hesiod, and admired the garden, and regretted the weather. The evenings would perhaps have begun to weigh, if someone had not suggested a game called Philanthropy. The rules of this game are very simple. One must justify things as they are by attacking things as they are. It is a philosophic game, perfectly suited to showing off a fine wit. It has even the thrill of risk, since it invites subversive ideas. But the point is always, of course, to achieve a resolution that will bring the argument right back where it began.

This distinguished party warms to the challenge. And how affecting it is to hear them, one after another, in the language of statesman and moralist, decry the sufferings of the poor, until it seems that the very table they sit around must be made into splints and crutches and the topiary garden planted in potatoes. Then, just when the pleasure of participation in this virtuous fantasy is at its height, that is to say, just when the temptations of virtue are most intense, then the player reveals the illusion: This “virtue” is not virtue at all, but an evil to be scrupulously avoided. A little thrill of relief passes over the company when their world is safely restored to them. But the risk is never as great as it may seem. Any strategy is sufficient in defending the moon from the wolves.

It is a distinguished company, and everyone seems willing to hold up his part in the game. Daniel Defoe, Bernard de Mandeville, Henry Fielding, Adam Smith (who did not understand the point of it, and was given a hearty cheer and sent off to bed). There is no need to observe chronology, since at this table Jeremy Bentham might find himself seated by Beatrice Webb, and Herbert Spencer by John Stuart Mill. This is only to say that their reflections on this subject accumulate rather than develop, in the manner characteristic of rationalizations. Their disputations produce a welter of harmonious contradiction, the sort of thing that happens when any argument is welcome that will prop a valued conclusion. So the centuries pass.

The influence of this genteel assembly can hardly be overstated. Only consider how important the notion of excess population—basically the artifact of an odd and unsavory history—has been to Britain, and therefore to the world. Malthus felt he observed the fact of population being restored to equilibrium with food supply in the misery of the poor, but at the time he wrote, the importation of wheat—bread was the food of the British poor—was restricted, and land had been converted to pasture which had formerly been used for growing food, and both industrial and agricultural workers had lost access to independent means of subsistence, the first by being crowded into urban slums where there was no corner of open land, the second by being crowded into rural slums where no bit of land was conceded to them. Social reformers early in this century wrote dreamily of the little garden plots of Belgian workers, who throve better on, of course, lower wages than their British counterparts. But the British laborer had no little plot of land. Irish immigrants shared quarters with their notorious pigs, which they slaughtered for food, but that was considered degraded. In fact, British workers, rural and urban, died of exclusive dependency on a meager wage, made up in part, especially among farm laborers, of parish relief, more parsimonious because it was paid by ratepayers rather than employers, and because, being “charity,” it always remained discretionary. The relation of population growth to the productivity of land, which Malthus tidily but meaninglessly described as increasing geometrically in the first case and arithmetically in the second, had nothing to do with the misery and vice he set out to account for. His was merely an early instance of the tendency to refer the consequences of a remarkably artificial situation to the hard laws of nature.

We have never ceased to talk about overpopulation, though true instances of it seem very rare. The English workingman Francis Place, having contrived to educate himself under astonishingly unfavorable circumstances, became the first writer in English to argue for birth control. He accepted Malthus’s view that workers were poor because there were too many of them, and he argued that their improvement lay in self-restraint. Of course, like poor people almost anywhere, they had children for their economic value. As late as the present century the prosperity of a family fluctuated with the number of employed people in it, and the early redundancy of the father, as well as such vicissitudes as sickness and injury, were more easily borne the more shoulders they fell on. Any glut of labor was the result of employing people from childhood, for sixteen hours a day or more, at wages that denied them any possibility of withholding their labor. A higher wage would have relieved the glut by allowing women to stay home with their new infants, or allowing families to keep older children at home to attend to younger children. Physical efficiency would have been enhanced at the same time.

But “working class” is the primary term in British social thought. The coercive implications of the phrase are glossed in every version and institution of the Poor Laws, right through Fabianism and the Welfare State, which is only the latest version of the ancient view that what the worker earns, his wage defined as subsistence, is not his by right, as property. The welfare system indeed assures that the wage will never amount to any specific sum of money but will be nuanced to provide subsistence itself, not in a money equivalent, however calculated. In other words, workers earn their existence by working. At the same time, their employment exists at the pleasure of those who employ, first of all, the government. The Welfare State, being designed for the employed, is designed for the less necessitous. Those who do not work are historically regarded with a sort of scandalized aversion, exactly like people without caste in a society based on caste.

Francis Place accepted blame for poverty on behalf of working p

eople, and accepted the notion that there could be an excess of people relative to their economic usefulness, and that that excess should be eliminated by sexual abstinence so that it need not be carried off by disease and starvation. He accepted the notion that there was a natural balance, a marketplace of survival glutted with laborers.

Darwin was likewise indebted to Malthus, and freely acknowledged his influence. Overbreeding relative to available food sources harrowed out those less well adapted to survive, in Darwin’s view. Herbert Spencer, who was to Beatrice Webb as Aristotle to Alexander, seized upon the idea immediately as a model drawn from nature, which justified just such horrors as had been Malthus’s point of departure one hundred years previously. Competition supposedly described the hardscrabble existence of the laboring classes, who sold their labor by the day and were constantly thrown out of work by a change of season or fashion, or the invention of a new machine. It was a commonplace that they helped one another as best they could through these disasters. The idea nevertheless had great impact because it made death a legitimate part of the social and economic order, a function rather than a malfunction of political economy, a measure of the extent to which the new industrial society cleaved to the ways of nature rather than departing from them. It affirmed the idea that there existed a human surplus, whose survival could only be secured at the cost of creatures worthier to survive. In such a context subsistence would be a positive reward, easily withdrawn, as in Darwinian nature.

The penchant for developing theories to account for suffering and death proved useful. Press and parliamentary reports of the Victorian period describe a system of exploitation which ravaged the culture, extruded every ounce of labor from those able to work—including small children and women recently delivered—starved them, beat them, poisoned them, housed them in cellars into which sewage drained from the streets, taking from them everything that could be taken, turning every good thing into a mode of exaction.

Housekeeping: A Novel

Housekeeping: A Novel Lila

Lila Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution

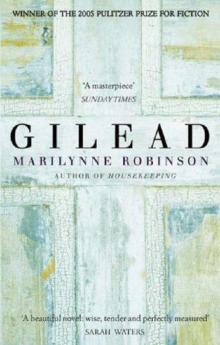

Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution Gilead

Gilead What Are We Doing Here?

What Are We Doing Here? Home

Home Jack

Jack Mother Country

Mother Country Lila: A Novel

Lila: A Novel Gilead (2005 Pulitzer Prize)

Gilead (2005 Pulitzer Prize)